Our Newsletters: From the Archives

It All Begins with Tree Rings

In this edition of the Midland newsletter, we take a closer look at wood grain, the beauty of which originates from a tree’s growth rings. Rings not only track a tree’s age, they record the conditions under which the tree lived each year of its life, in rain or drought, even if it survived a fire. When grain is on view, the story of the tree lives on in the cabinetry and millwork.

Shown below, a close-up of the rift sawn white oak used in the wet bar (pictured above) created for a showcase San Francisco home. You can clearly see the vertical nature of the cut and the grain pattern, which embodies the linear, sleek look desired in today’s modern styling.

In terms of working with the two grain choices, closed grain has a smoother surface, while some open grain varieties need a filler to flatten and smooth their surfaces.

The Final Look: A Cut Above the Ordinary

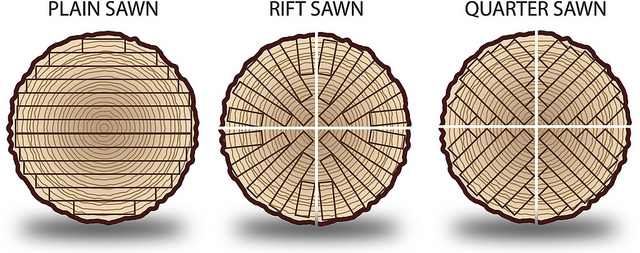

When a tree is cut, the pattern — or figure, as it’s called in woodworking — represents portions of the tree’s annual rings. Plain sawn is the most common cut for standard uses, while specialty cuts like quarter and rift sawn are the primary choices for producing stable, strong wood with straight and prominent grain lines. The sought-after more linear nature of rift sawn wood is the result of milling the lumber perpendicular to the growth rings at an angle of between 45 to 75 degrees, which exposes the grain evenly on all sides of the lumber. The most expensive cut, rift sawn was commonly used in Mission and Craftsman design and remains a favorite among artisans.

Wood Grain and Architectural Veneers

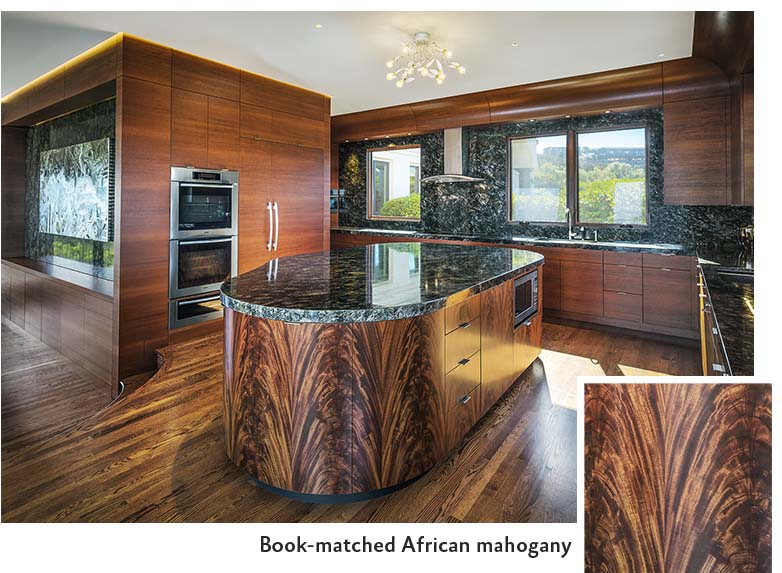

Book-matching veneer is an exacting process: like facing pages in a book, the two veneer panels must mirror each other exactly. It’s worth the effort: The result is a visual treat.