The appliance garage shown here is integrated into the range-top backsplash.

The Goal Is to Maximize Both Space and Storage

Forget the concept of spring cleaning. Keeping clutter out of sight is a year-round pursuit as more of Midland’s clients opt for the sleek, clean lines of minimalist design. What they seek: updated solutions for the adage “a place for everything and everything in its place.”

The flat facade and refined aesthetic that are the hallmarks of minimalist home design pose a problem when it comes to all the “stuff” we depend on: How to incorporate those necessary things into a modernist landscape that is anathema to clutter.

For Midland, it means translating the vision of simplicity into a functional reality. One common solution is the appliance garage, now a staple design addition for ensuring that small appliances are at hand but tidily out of sight. The one shown above is integrated into the range-top backsplash.

Now You See It, Mostly You Don’t

Just as we engineered the fireplace surround in this photo and the next to hide and reveal a flat-screen TV monitor — while maintaining the clean lines of the structure itself — we are reinventing casework for a new generation of hidden functional spaces.

One of our current projects is a pair of bi-folding pocket doors built into a floor-to-ceiling opening. Pocket doors are commonly used as a space saving feature, and that’s true in this case too, but with a challenging difference: They shouldn’t look like doors to anyone passing by.

The point of the project is two-fold. The space behind the doors will hold the family washer and dryer. And because this laundry area is located in a public thoroughfare — the home’s main hallway — the client wants the doors to be as invisible as possible. There should be no inkling that equipment sits behind the faux “wall.”

In other words, Midland is creating hidden doors for a hidden space.

“Our job is to engineer casework that looks like a regular wall panel,” says Jeb Boynton, the job’s project manager. “When the doors are closed, you won’t see the hardware — or even realize that the doors are there.”

Straightforward, right? Not at all.

The Challenge of Simplicity

As Boynton notes, it is one thing to design doors that look like wall panels. It is another to engineer those panels to ensure that these “invisible doors” function as they should, and do so seamlessly through years of heavy use.

One challenge is the hardware: Most designs today, including this one, call for concealing hardware, a design tenet of the sleek modernist look. In this case, the hinges and door guides are not integrated into vertical side jambs, as they normally would be, but into the floor and ceiling. This switch from conventional to unconventional door function is an engineering stretch, even when calling on the fine European hardware that Midland uses.

“Sophisticated or not, hardware still has limitations,” Boynton says, a handicap that adds to the challenge of engineering something that needs to look “simple” to the eye, but which, in reality, must be highly functional. As a result, it is not unusual for Midland to custom make its own hardware to fit the design concept.

From a 2-Dimensional Concept to Reality

“Our clients expect a high level of functionality from Midland’s products,” says Boynton. “Incorporating unique design elements into the functionality of a piece takes a lot of detailing, a lot of thought and engineering.”

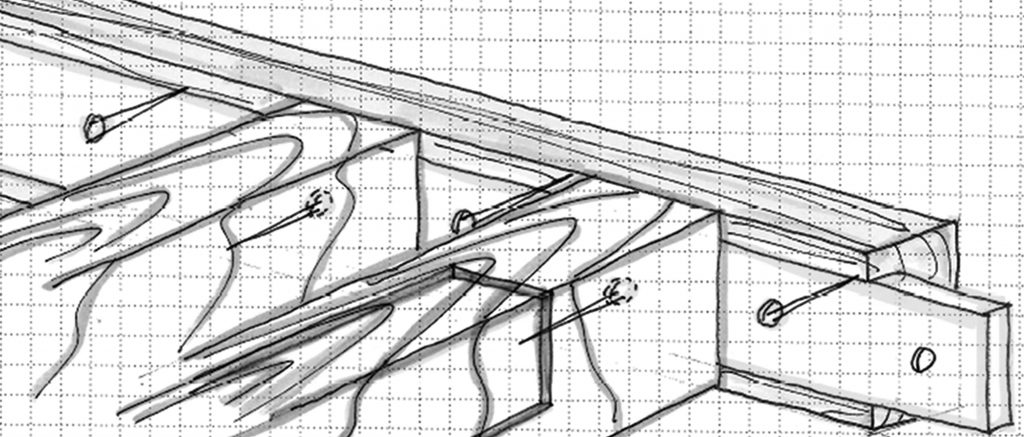

What Midland receives from an architect or lead designer is often a concept sketch. “We have to figure out how to make that two-dimensional concept work and, most importantly, to engineer it to function as required.” The trick: Midland “dissects” the concept sketch to create a cross-section view.

“By seeing the cross-section we can determine how to make the design work from the standpoint of fabrication,” says Boynton.

An off-road motorcycle enthusiast, Boynton sees parallels between fabricating simple looking but high-performance casework and high-power performance engines on off-road race bikes.

“A motorcycle engine needs to take up limited space. It needs to be lighter and more powerful not heavier and bigger. So while they may look simple on the outside, often like a small barrel on the side of the chassis,” says Boynton, “if you cut the engine case and cylinder in half you see the intricate, very complicated mechanisms required for these modern machines.”

“Our job is to engineer casework that looks like a regular wall panel.”

It is one thing to design doors that look like wall panels. It is another to engineer those panels to ensure that they function as they should.

What Midland receives from an architect or lead designer is often a concept sketch. “We have to figure out how to make that two-dimensional concept work.”